- Averchenkova A, Fankhauser S, Finnegan J (2020) The impact of strategic climate legislation: evidence from expert interviews on the UK Climate Change Act. Climate Policy. 21(2), 251-263. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1819190

- Grantham Research Institute at the London School of Economics and Climate Policy Radar (2023) Climate Change Laws of the World. https://climate-laws.org and https://app.climatepolicyradar.org/search

Innovations in Climate Change Acts: Kenya, Uganda and Nigeria in focus

This article was written by Catherine Higham, Anirudh Sridhar, and Emily Bradeen from the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics (LSE).

The article was produced in collaboration with the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) to examine developments in climate legislation in Africa ahead of the 66th Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference in Accra, Ghana, from 30 September - 6 October 2023.

The authors are grateful for the insights and review provided by the following experts from the countries considered in this article: Hon. Christine Kaaya Nakimwero, Member of Uganda’s Parliament and Member of Parliamentary Climate Change Committee, Hon. Samuel Onuigbo, Former Representative of Nigeria’s House of Representative and Chair of Nigeria’s Climate Parliament, Dr Temitope Onifade of Bristol University, Daphne Kamuntu and Bridget Ampurira, Greenwatch Uganda, Pauline Makutsa, Adaptation Consortium. The article also benefited from reviews by Olivia Rumble of Climate Legal and Tiffanie Chan of the Grantham Research Institute.

Introduction

Around the world, over 1,000 laws related to climate change have been passed by legislatures in at least 170 countries. These laws are captured in the Climate Change Laws of the World Database maintained by the Grantham Research Institute at the LSE. The database reveals a variety of legal designs that respond to the common threat of climate change, while accounting for context specific challenges and different traditions of governance. Comparative analyses of these climate laws (Sridhar et al 2022; Scotford and Minas 2018) enable knowledge and exchange between actors involved in climate law-making.

The global body of climate laws is hugely varied, but past research has identified two broad categories:

- Overarching framework laws: These laws offer “a unifying basis for climate change policy, addressing multiple aspects or areas of mitigation or adaptation (or both) in a holistic and overarching manner”. (Sridhar et al, 2022; See also Townshend et al, 2011; Clare et al, 2017; Fankhauser et al, 2014). Such laws typically set the agenda for a country's climate policy response, often include provisions establishing institutions and processes to enable government action on climate change, and frequently include specific policy instruments such as carbon pricing schemes and fossil fuel phaseouts. Such laws can be valuable both for their narrative signalling and for their ability to make “action on climate change more predictable, more structured and more evidence-based” (Averchenkova et al, 2020). Around the world, there are now close to 60 such laws from at least 53 countries, 15 of which are in the Commonwealth.

- Sectoral laws: These laws aim to address climate issues in a given sector of the economy such as industry, energy, transport or finance (Sridhar et al, 2022). Many such laws are introduced through amendments to pre-existing legislation. Examples include environmental impact assessment laws that are updated to include provisions on considering the implications of a proposed project on climate change, (see: Impact Assessment Act (S.C. 2019, c. 28, s. 1)), energy laws upgraded to target climate mitigation in energy conservation policies (see: Energy Conservation Act 2022 Amendment), and finance laws amended to include climate change risks and opportunities (see: Financial Sector (Climate-related Disclosures and Other Matters) Amendment Act 2021).

Both types of legislation will be needed to address climate issues. However, in many cases, the introduction of a framework law will help facilitate the effective development of sectoral laws, particularly where a system-wide approach is needed to ensure that complementarities and tradeoffs are well understood.

With that in mind, this article provides an overview of some of the key functions of framework laws before taking a closer look at laws from the Commonwealth countries of Kenya, Uganda, and Nigeria. We have elected to focus on these case studies for two reasons. Firstly, because these laws are in general less widely discussed in academic and policy literature. Secondly, because each of these three countries is highly vulnerable to climate change but has made a relatively small per capita contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions, and as a result, they offer examples of framework laws where climate change adaptation approaches have been “especially prioritised” or given similar weight to mitigation (Rumble, 2019), which is often the primary priority in more well-studied laws from the Global North.

What are governance functions of framework laws?

Climate change generates a set of governance challenges that are unlike other environmental problems in scale and scope. Sources across the economy contribute to the problem, the pervasive nature of its impacts are felt throughout society, and a wide range of actors must be recruited to manage those impacts. In order to tackle such a complex problem, a framework law is often required to facilitate consensus building around strategies and targets (among potential winners and losers), mainstream climate-conscious decision making into the regular functioning of line ministries, and coordinate national and subnational governments in transformational restructurings. By creating institutional arrangements requiring different actors to engage with climate policy, framework laws facilitate self-organisation across different sectors.

Despite the consistency of these governance problems across countries, they can only be tackled by a careful study of how they manifest in a particular political and economic context. For instance, the degree of autonomy that subnational governments enjoy in a country will bear significantly on its style of climate federalism; and the size and nature of the economy will determine the effort required to restructure the economy to a low carbon one.

Considering the ‘governance functions’ of framework laws is a way to reconcile the common governance problems posed by climate change and the specific ways in which those problems should be approached in given contexts. The paper that introduced this concept defines them as ‘the necessary and desirable roles of the institutional structures and processes governments put in place in addressing the specific challenges to society thrown up by climate change’ (Sridhar et al, 2022). The assumption is that climate change will necessitate certain common roles for any government; but the nature, extent, and relative priority of those functions will vary. For instance, given the fast-changing nature of threats, solutions, and opportunities presented by climate change, knowledge gathering will be a key prerequisite for any government to commit to strategic and long-term actions. But whether the focus of knowledge gathering is more on low carbon development opportunities, compliance with emissions standards, or knowledge-gathering on risk and resilience may be based on the relative level of economic development and geographic vulnerability, as well as on countries’ needs to respond to transparency obligations under international climate conventions.

- Ecologic Institute (2023) Climate Framework Laws Info-Matrix. Ecologic Institute, Berlin. https://www.ecologic.eu/19320#:~:text=The%20Climate%20Framework%20Laws%20Info,countries%20plus%20the%20United%20Kingdom

- Sridhar A, Averchenkova A, Rumble O, Dubash NK, Higham C, Gilder A (2022) Climate Governance Functions: Towards Climate Specific Laws. Policy brief, Centre for Policy Research. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Climate-Governance-Functions_17_Nov_22.pdf

- World Bank (2020) World Bank Reference Guide to Climate Change Framework Legislation. Equitable Growth, Finance and Institutions Insight – Governance. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/34972

How are these functions met in Kenya, Uganda, and Nigeria’s legislation?

As in many other countries around the world, the three case studies in this piece have features that aim to address the functions discussed above through different mechanisms, and with a different balance of priorities. The table below maps a few key features of each law to the governance function they attempt to serve. We then take a closer look at how each country has handled a specific function, considering Kenya’s approach to multi-level coordination, Uganda’s approach to accountability, and Nigeria’s approach to mainstreaming. Each offers an interesting example for other legislators to consider, although in the case of Uganda and Nigeria’s relatively new laws, the long-term impacts of the provisions remain to be seen.

Table 1. Certain Examples of Governance Functions in Climate Laws. Having problems viewing this table? Download a copy.

| Governance function | Kenya’s Climate Change Act, 2016 | Uganda's National Climate Change Act, 2021 | Nigeria's Climate Change Act 2021 |

| Narrative and high-level direction-setting | Aims to enhance climate change resilience and low carbon development | Advances climate action and building climate resilience, giving the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement force of law. | Aims to achieve low greenhouse gas emission objectives, inclusive green growth, and sustainable economic development. |

| Strategy articulation | Establishes that the Cabinet Secretary for the National Treasury must formulate a National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP). | Mandates a Framework Strategy on Climate Change that identifies mitigation and adaptation priorities | Establishes a National Climate Change Council (NCCC) to articulate five-year climate action plans |

| Knowledge and expert advice | Climate Change Directorate (CCD) provides analytical support on climate change to sector ministries, agencies and county governments and serves as the national knowledge and information management centre for collating, verifying, refining, and disseminating knowledge and information on climate change. | National Climate Change Advisory Committee provides independent technical advice to the Policy Committee on the Environment and Minister. | Secretariat to the NCCC collects data and disseminates information on climate risks and carbon budgets and advises the NCCC on climate science to inform the NCCC’s recommendations on climate change measures. |

| Integration and Mainstreaming | CCD ensures the mainstreaming of climate change by national and county governments. All public entities are responsible for integrating the climate change action plan into sectoral strategies and other projects. | Establishes lead agencies to create standards for reducing vulnerabilities and building resilience. Lead agencies coordinate the mainstreaming of climate change action plans across government. | Federal Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs) will create climate change ‘desks’ to monitor the integration of climate change into core mandates. Private entities must effectuate measures to align with national plans. |

| Coordination | CCD provides an overarching national climate change coordination mechanism and advises national and county governments on climate change response measures. | Each district’s Natural Resources Department must coordinate with the Climate Change Department and the Ministry for local governments over issues related to climate change. | Requires the NCCC to coordinate the implementation of sectoral targets and guidelines to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. |

| Stakeholder engagement and alignment | CCD will produce an annual public engagement strategy to inform the public on climate actions plans and how they can contribute. | The Climate Change Department will promote multi-stakeholder and public participation in developing responses to the impacts of climate change. | Action Plans must be published to the general public for a consultation period before they are approved by the government. |

| Finance mobilisation and channelling | Establishes a Climate Change Fund to finance priority climate change actions. | Mandates the Finance Minister to direct financing and incentives for climate action. | Establishes a Climate Change Fund and plans to develop a carbon tax. |

| Oversight, accountability, and enforcement | The National Environmental Management Authority will monitor whether public and private entities are complying with their climate change duties and will prepare an annual report for the CCD. The CCD will provide an annual report to the National Assembly. | Litigation may be filed before the High Court of Uganda against the government, individuals, or private entities whose actions/omissions threaten climate change action. | NCCC must approve and oversee the implementation of the Action Plans, and report on progress. |

- Averchenkova A, Fankhauser S and Finnegan JJ (2021) The influence of climate change advisory bodies on political debates: evidence from the UK Committee on Climate Change. Climate Policy. 21(9), 1218-1233. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2021.1878008

- Averchenkova A, Lazaro L (2020) The design of an independent expert advisory mechanism under the European Climate Law: What are the options? London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/GRI_The-design-of-an-expert-advisory-mechanism-under-the-European-Climate-Law_What-are-the-options.pdf

- Carrick J (2022) Governance Structures and practices of climate assemblies. KNOCA Briefing No. 6. European Climate Foundation. https://knoca.eu/app/uploads/2022/09/KNOCA-Briefing-8-Governance-Structures-and-Practices-of-Climate-Assemblies.pdf

- Dudley H, Jordan AJ, Lorenzoni I (2021) Independent expert advisory bodies facilitate ambitious climate policy responses. ScienceBrief Review. https://sciencebrief.org/uploads/reviews/ScienceBrief_Review_ADVISORY_BODIES_Mar2021.pdf

- Higham C, Averchenkova A, Setzer J and Koehl A (2021) Accountability Mechanisms in Climate Change Framework Laws. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Accountability-mechanisms-in-climate-change-framework-laws.pdf

- Langkjær F (2021) How can climate assemblies be integrated into the policy processes? KNOCA Briefing No. 2. European Climate Foundation. https://knoca.eu/app/uploads/2021/12/HOW-CAN-CLIMATE-ASSEMBLIES-BE-INTEGRATED-INTO-THE-1.pdf

- Mwanga E (2019) The Role of By-Laws in Enhancing the Integration of Indigenous Knowledge. Carbon & Climate Law Review. 13(1), 19-30. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26739641

- Rumble O (2019) Facilitating African Climate Change Adaptation Through Framework Laws. Carbon & Climate Law Review. 13(4), 237-245. https://doi.org/10.21552/cclr/2019/4/4

Multi-level coordination and mainstreaming in Kenya’s Climate Change Act 2016

Kenya’s subnational governments, called counties, are semi-autonomous in nature. This has led to the Climate Change Act 2016 (CCA) paying particular attention to climate federalism (Fenna et al, 2023). The CCA aims to “integrate climate change into the exercise of power and functions of all levels of governance”. To do so, it provides that a “county government may enact legislation that further defines implementation of its obligations under this Act." In response, as expert Pauline Makutsa confirmed, 45 out of 47 counties in Kenya have passed their own climate laws. This is an innovative example of legislative design that is friendly to climate federalism by allowing for context-based experimentation (Adaptation Consortium, 2019).

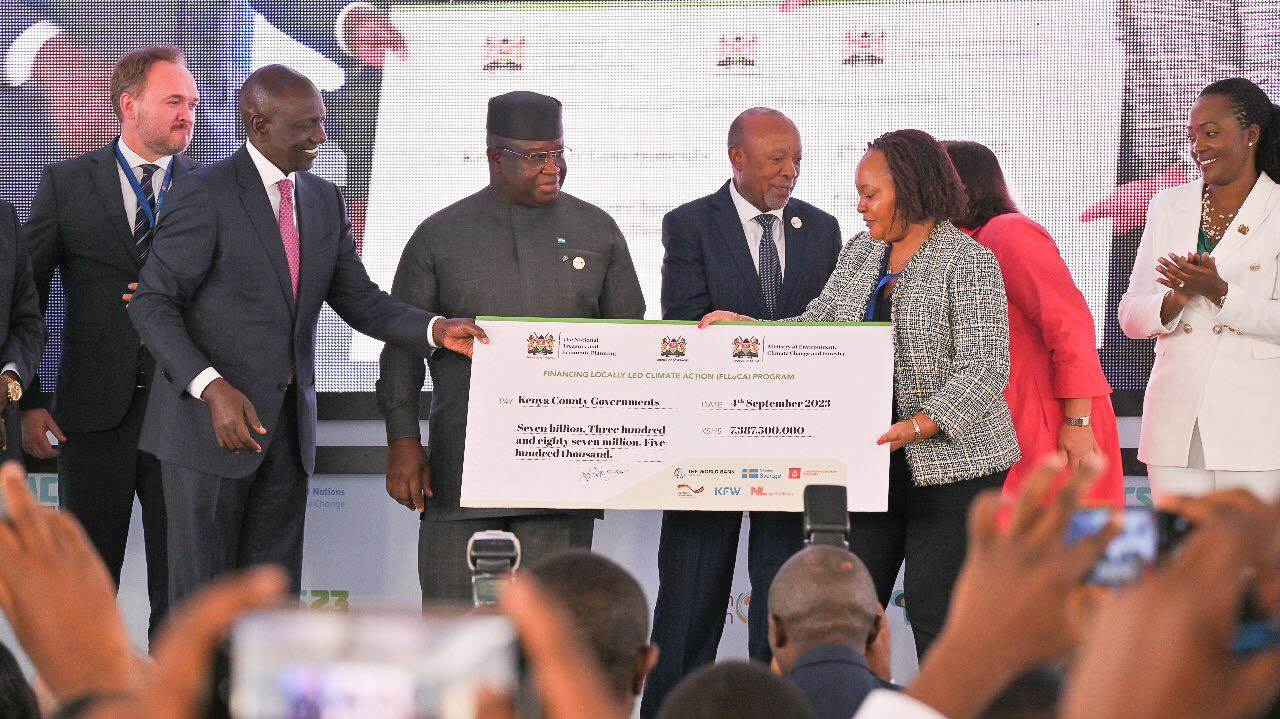

Kenya’s county laws put in place innovative modes of adaptation governance, fostering unprecedented levels of community involvement in climate action. One example is the County Climate Change Fund (CCCF) mechanism, which has been worked into several county-level climate laws.

The CCCF is a tool to mainstream climate change into development and planning decisions of counties (Kiiru and Elhadi, 2019). The goals of the CCCF are to establish robust feedback loops between communities and government and to commit a minimum of 2% of the county budget to climate action.

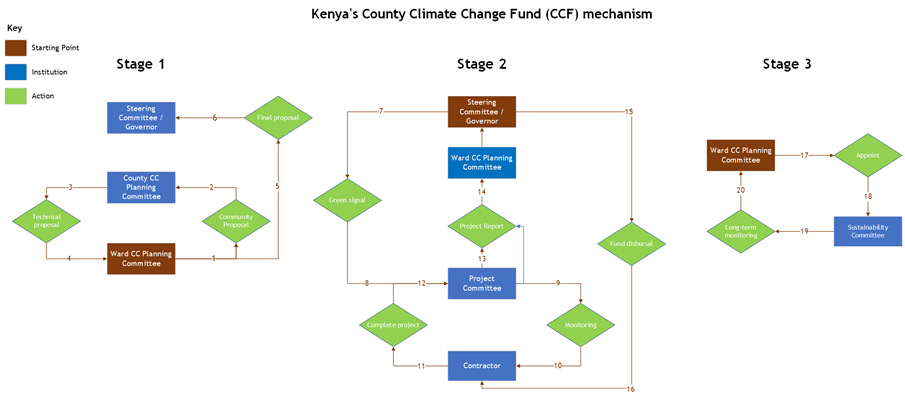

The process works through three institutional levels. The County Climate Change Planning Committee (CCCPC) oversees all adaptation-related projects in a given county. A Ward Climate Change Planning Committee (WCCPC) drafts proposals on adaptation needs on the ground. The Steering Committee (SC), which is sometimes chaired by the Governor, is in charge of oversight, and has the final say on fund allocation for an adaptation project, after it has been approved by County Assembly members.

The Secretary of the WCCPC liaises with the CCCPC and SC. The WCCPC is gazetted and financed, and has representatives elected from villages, including women, the differently abled, and members from diverse sectors, such as livestock management and farming (Kiiru and Elhadi, 2019). It regularly discusses climate-related problems and potential solutions, which are articulated into official ‘Community Proposals’. The proposal is vetted by the CCCPC for its technical viability, whereupon it becomes a ‘Technical Proposal’. The ‘Technical Proposal’ is then re-sent to the community, to ensure that that is what they originally wanted.

A contractor is then identified to implement the proposal, for example, building a dam. A temporary ‘Project Committee’ (PC), composed of the WCCPC and a Technical Officer from the CCCPC, monitors every step of the project. The PC ratifies the completion of the project, whereupon the SC releases funds to defray the construction charges. The project is then handed over to the County Government which launches and bequeaths it to the community. The community then elects a ‘Sustainability Committee’ that manages the use and maintenance of the investment, with occasional, need-based interventions of the County Government.

Kenya’s CCA, and the subnational climate governance processes it facilitates, has been one of the most successful examples of climate federalism (Wendo and Crick, 2020). Through the county climate laws and the CCCF mechanism they formalise, the CCA stands as an example of how national laws that encourage local experimentation can lead to climate governance that addresses real problems on the ground.

Accountability and judicial oversight in Uganda’s National Climate Change Act 2021

One innovative provision in Uganda’s Climate Change Act 2021 (the Act) is Section 26 on “climate change litigation”. This provision gives standing for any person to bring a case before the High Court of Uganda against any individual or entity who, by act or omission, threatens efforts towards climate change adaptation or mitigation. Cases can be brought against government officials or private individuals. In cases where the alleged act or omission has caused “loss and damage” to an applicant, damages may be awarded, in line with the Polluter Pays Principle.

As Ugandan Member of Parliament Hon. Christine Kaaya Nakimwero confirmed, the provision was introduced to create accountability for public officials, and to ensure that those looking to invest in the country are aware that climate action and the need to avoid environmental damage must be taken seriously. Section 26 connects the domestic legislation to the global phenomenon of climate change litigation, which has seen communities and individuals around the world turning to the courts to influence the outcomes and ambition of climate governance (IPCC, 2022; Setzer and Higham, 2023).

Hon. Christine Kaaya Nakimwero, a Member of Uganda's Parliamentary Committee on Climate Change

It is clear that such accountability for the implementation of Uganda’s Act is critical. A report from Uganda’s Parliamentary Committee on Climate Change published in August 2022 expressed concern about the “inadequate implementation” of the Act, a situation that still persists. To date, no new litigation has been filed using s.26 of the Act. However, Uganda has seen several earlier examples of climate change litigation, including the rights-based case of Tsama Williams and Ors v Attorney General and others, in which the applicants alleged failures on the part of the government to protect them from climate change impacts, as well as the 2012 case of Mbabazi and Ors v Attorney General and the National Environment Management Authority, which concerned the insufficient implementation of national climate policy frameworks. Both cases, which are supported by the NGO Greenwatch, are pending a court judgment and hearing respectively, and the pleadings have been amended to take account of the 2021 Act. A third case concerning forest management also raises relevant issues.

Such cases may lay the groundwork for civil society or affected communities to bring future cases under Section 26. However, there will be challenges to bringing such litigation, including the potential for significant costs to be imposed on litigants (Mwesigwa and Mutesasira, 2021). Litigation also does not in itself fully serve the accountability and transparency function for the targets of the Act, without accompanying provisions on transparency and reporting duties on government.

It should also be noted that in the parliamentary report referred to above, one of the primary reasons for the “inadequate implementation” of current legal frameworks on climate action is the lack of financial and other resources. As noted in the table above, the Act charges the Minister of Finance to direct resources towards climate action. It is possible to imagine a case under s.26 in which the Minister is charged with failing to discharge this duty if the implementation of the law remains under resourced. However, any such action would need to be understood against the backdrop of the ongoing failure of developed country parties to the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement to fulfill their own obligations with regard to climate finance (Higham et al, 2022).

Mainstreaming climate considerations in the private sector: Nigeria’s Climate Change Act 2021

Prior to the 2021 Climate Change Act (the Act), climate change action in Nigeria focused to a large extent on climate resilience. However, while resilience remains one of Nigeria’s fundamental climate objectives, the Act also sets a target to achieve net zero GHG emissions between 2050 and 2070. This emphasis on mitigation is highly significant given Nigeria’s status as a major oil exporter. It also reflects the fact that one of the key objectives of the Act is to facilitate the achievement of Nigeria’s international climate commitments, including those under the Paris Agreement (NCCC, 2023).

Section 24 of the Act sets out a bold provision on the climate obligations of private entities that aims to mainstream climate considerations and transition planning in the private sector, with a focus on mitigation measures and alignment with national emissions goals. This provision aligns with trends in legislated corporate climate obligations that are emerging globally, as countries consider the legal pathways to mandating corporate and non-state actors to advance climate action.

In contextualizing the origins of Section 24, Representative Samuel Onuigbo, a former member of the House of Representatives who sponsored the Bill, stated that the goal was to ensure that “all hands are on deck” to achieve the country’s emissions reduction targets. One of the intentions of Section 24 is to help ‘future-proof’ the activities of the country’s private sector by requiring a broad swathe of private entities to engage with the Act. Representative Onuigbo stated that it was better to ensure that such action is mandated through the legislation even at this early stage in the development of mitigation actions “because if it’s not [there], it cannot be enforced”.

Rep. Onuigbo with the 9th Speaker during a climate change event in a conference room at the National Assembly of Nigeria.

However, there have been challenges to implementing the Act and it remains unclear how private entities will be able to implement Section 24 without further guidance from the government. The finalised National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP) has not yet been submitted to the National Assembly for approval (Aileman, 2023), so it is unlikely that companies and other private entities have begun the process of implementing Section 24 of the Act, as these measures must align with the NCCAP’s targets.

Smaller entities may struggle to comply with Section 24 if they face capacity constraints in conducting analyses required to inform their contribution to achieving the NCCAP. At this stage, it is unclear precisely what form private entities’ climate measures and reports must take, the degree to which measures must cover adaptation as well as mitigation, and in what circumstances emissions inventories covering scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions need to be developed. Further guidelines or regulations, or explanatory notes, issued by the NCCC or the government on these matters will be essential to ensuring that Section 24 can be complied with to effectively advance climate action in Nigeria. Incorporating local contexts and regional approaches to how business is conducted may also prove useful to facilitating compliance across Nigeria’s federations and regional governments given the size and diversity of the population.

Through Section 24, Nigeria has adopted a strong regulatory approach to address the need to accelerate private sector climate action, an issue that legislators and regulators around the world are currently grappling with. It has yet to be seen whether this approach will be effective; however, it is certainly worth following how the implementation of these provisions develops over time.

Balancing resilience and low carbon development

A review of these three country case studies reveals interesting approaches to balancing resilience-building and curbing GHG emissions. This is a shared challenge for developing economies in the Sub-Saharan African region and elsewhere, which have produced relatively low quantities of greenhouse gas emissions, but whose populations are likely to suffer disproportionately from the impacts of climate change, having “minimal adaptive capacities and resources to respond to the[se] challenges” (Rumble 2019, 238).

Adaptation governance generates many challenges that are distinct from mitigation governance (Kweyu et al, 2023; Ruhl, 2010). For instance, weather events need to be understood as climate related and issues on the ground need to be raised through bottom-up processes - as we observed in the context of Kenya’s county laws. These are often more locally specific operations than the often top-down process of emissions management.

All three of these laws include provisions on adaptation management to varying degrees. Yet as Clarice Wambua has highlighted, one of the ways in which the Kenyan law can be seen as pioneering is its focus on low carbon development (Wambua, 2019), a concept that can also be found in both Uganda and Nigeria’s legislation, although in Nigeria’s law the term used is “green growth”. This trend might be influenced by the Paris Agreement and international efforts enjoining collaborative attitudes to mitigation among developing countries.

There has also been a shift in narrative to recognise that strong signaling (especially in law) about mitigation ambition may attract green investment and render developing economies more competitive in future energy markets (Nachmany et al, 2017). Decoupling economic growth from high carbon pathways requires initial knowledge gathering and planning (UNECA, 2016). As in the Nigerian Act, this involves the meticulous process of “mainstreaming of climate change into the national development plans and programmes”. Careful consideration of the best ways to introduce or strengthen ‘governance functions’ to address both aspects of the climate challenge is critical to ensuring effective legislative design.

- OECD (2021) Strengthening adaptation-mitigation linkages for a low-carbon, climate-resilient future. OECD Environment Policy Papers, 23. OECD Publishing: Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/6d79ff6a-en.

- Rumble O (2019) Facilitating African Climate Change Adaptation Through Framework Laws. Carbon & Climate Law Review. 13(4), 237-245. https://doi.org/10.21552/cclr/2019/4/4

- Wambua C (2019) The Kenya Climate Change Act 2016: Emerging Lessons from a Pioneer Law. Carbon & Climate Review. 13(4), 257-269. https://doi.org/10.21552/cclr/2019/4/6

Conclusion

By looking at the examples of existing climate laws, legislators and policy-makers can enhance their understanding of some of the key challenges that must be addressed in domestic climate policy responses and gain inspiration from innovative approaches that may be replicated elsewhere. However, in the development of any new climate legislation, careful consideration must be given to domestic context and needs. While economic growth remains a primary objective, particularly in the developing world, it is increasingly recognised that long-term growth requires responding to climate change. A framework law, including some or all of the functions discussed above, can support such a response, as it facilitates strategising mitigation pathways that are economy-friendly and attempts to synergise adaptation and mitigation goals through a focus on climate-resilience and low-carbon development.

References

Adaptation Consortium (2019) Review of the Legal and Financial Framework of the CCCF Mechanism: Final Report. Adaptation Consortium. http://site.adaconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Review-of-the-Legal-and-Financial-Framework-of-the-CCCF-Mechanism.pdf

Aileman A (2023) Buhari approves work plan for climate change council. Business Day. https://businessday.ng/news/article/buhari-approves-work-plan-for-climate-change-council/#google_vignette

Averchenkova A, Fankhauser S, Finnegan J (2020) The impact of strategic climate legislation: evidence from expert interviews on the UK Climate Change Act. Climate Policy. 21(2), 251-263. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1819190

Clare A, Fankhauser S, Gennaioli C (2017) The national and international drivers of Climate legislation, in Averchenkova A, Fankhauser S, Nachmany M (eds.) Trends in Climate Change Legislation. London: Edward Elgar

Fankhauser S, Gennaioli C, Collins M (2014) Domestic dynamics and international influence: What explains the passage of climate change legislation? Working Paper No. 156, Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy and Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. https://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Wp156-Domestic-dynamics-and-international-influence-what-explains-the-passage-of-climate-change-legislation.pdf

Fenna A, Jodoin S and Setzer J (2023) “Climate Governance and Federalism: An Introduction,” in Fenna A, Jodoin S and Setzer J. (eds) Climate Governance and Federalism: A Forum of Federations Comparative Policy Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–13. doi: 10.1017/9781009249676.002.

Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment [GRI] (2022) What is the Polluter Pays Principle? Commentary, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, LSE. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/explainers/what-is-the-polluter-pays-principle/

Grantham Research Institute at the London School of Economics and Climate Policy Radar (2023) Climate Change Laws of the World. https://climate-laws.org and https://app.climatepolicyradar.org/search

Higham C, Higham I, Narulla H (2022) Submission to the High-Level Expert Group on the Net-Zero Commitments of Non-State Entities. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/publication/submission-to-the-high-level-expert-group-on-the-net-zero-emissions-commitments-of-non-state-entities/

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC] (2022) Summary for Policymakers. Mitigation of Climate Change Working Group III contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [ed.s Skea J, Priyadarshi R S, Reisinger A, Slade R, Pathak M et al.]. Geneva: World Meteorological Organization. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGIII_SPM.pdf

Kiiru J and Elhadi Y (2019) County Climate Change Fund Mechanism: Building Resilient Communities, Promoting Sustainable Economic Growth. Adaptation Consortium. http://site.adaconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/CCCF-Mechanism-summary.pdf

Kweyu RM, Asokan SM, Ndesanjo RB, Obando JA and Tumbo MH (2023) Climate Governance in Eastern Africa: The Challenges and Prospects of Climate Change Adaptation Policies. State Politics and Public Policy in Eastern Africa. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13490-6_16

Mwesigwa SAK and Mutesasira PD (2021) Climate Litigation as a Tool for Enforcing Rights of Nature and Environmental Rights by NGOs: Security for Costs and Costs Limitations in Uganda. Carbon & Climate Law Review. 15(2), 139-149. https://doi.org/10.21552/cclr/2021/2/5

Nachmany M, Fankhauser S, Setzer J and Averchenkova A (2017) Global Trends in Climate Change Legislation and Litigation. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. http://archive.ipu.org/pdf/publications/global.pdf

National Council on Climate Change [NCCC] (2023) Regulatory Guidance on Nigeria’s Carbon Market Approach. https://natccc.gov.ng/publications/NCCC%20Regulatory%20Guidance%20on%20Nigeria’s%20Carbon%20Market%20Approach.pdf

Ruhl JB (2010) Climate Change Adaptation and the Structural Transformational of Environmental Law. Environmental Law. 40(2), 363-435. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43267611

Rumble O (2019) Facilitating African Climate Change Adaptation Through Framework Laws. Carbon & Climate Law Review. 13(4), 237-245. https://doi.org/10.21552/cclr/2019/4/4

Setzer J and Higham C (2023) Global Trends in Climate Change Litigation: 2023 Snapshot. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Global_trends_in_climate_change_litigation_2023_snapshot.pdf

Sridhar A, Averchenkova A, Rumble O, Dubash NK, Higham C, Gilder A (2022) Climate Governance Functions: Towards Climate Specific Laws. Policy brief, Centre for Policy Research. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Climate-Governance-Functions_17_Nov_22.pdf

Scotford E and Minas S (2018) Probing the hidden depths of climate law: Analysis national climate change legislation. Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law. 28(1), 67-81. https://doi.org/10.1111/reel.12259

Townshend T, Fankhauser S, Matthews A, Feger C, Liu J, and Narciso T (2011) Legislating climate change on a national level. Environment. 53, 5-16. https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/venv20/current

Wambua C (2019) The Kenya Climate Change Act 2016: Emerging Lessons from a Pioneer Law. Carbon & Climate Review. 13(4), 257-269. https://doi.org/10.21552/cclr/2019/4/6

Wendo H and Crick F (2020) Readying Counties for the County Climate Change Fund Mechanism (CCCF). Adaptation Consortium. https://adaconsortium.org/readying-counties-for-the-county-climate-change-fund-mechanism-cccf/

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa [UNECA] (2016) Greening Africa’s Industrialisation: Economic Report on Africa. United Nations. https://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/fullpublicationfiles/era-2016_eng_rev6may.pdf